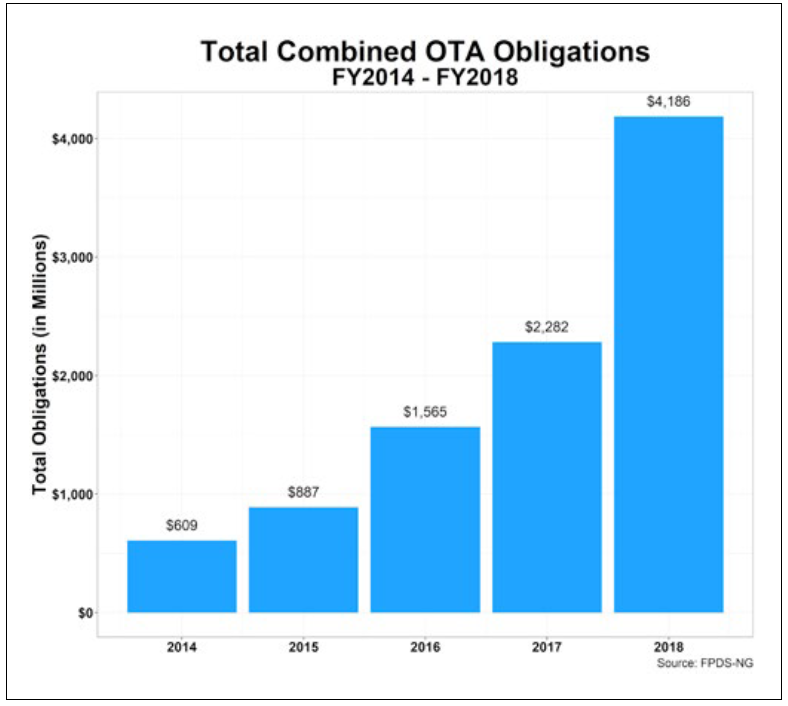

If you are on the lookout for the latest trends in government contracting, you have probably heard that Other Transaction Agreements (“OTAs”) are all the rage – for both industry newcomers and veterans, as well as some of the largest government agencies. While OTAs are not new, obligated funds have grown from roughly $600 million five years ago to almost seven times that in 2018.

In contrast to what some may fear, OTAs are not a replacement tool for the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), nor are they specifically designed solely for the non-traditional government contractor (NDC). In the Department of Defense (DoD), OTAs are designed to increase the speed and efficiency of getting mission-critical technology to the warfighter1. It is the comparative speed of these transactions, coupled with the freedom from competition requirements—protests generally— and the ability to permit more advantageous IP/data rights that make them so attractive to the government buyer, resulting— at least in part—in their more recent proliferation.

Congress has also played a part in the dramatic uptick of OTAs by permanently codifying for DoD OTA prototype authority; broadening the use OTAs for prototypes; expanding the definition of the term “non-traditional defense contractor” to

include small businesses and non-profits; making it easier to issue follow-on production contracts; and establishing an actual preference for OTAs for prototyping.

The outlook for OTAs seems bright and the use of these contracts is expected to continue to grow. However, the potential shift in the federal acquisition paradigm (at least with respect to R&D and prototyping) and the varying nature of these procurements have also created several challenges for federal contractors and for government personnel. In this article, we focus on these challenges.

Areas of concern include (1) the potential lack of competition in a sector where stewardship of taxpayer dollars is a cornerstone, and where fraud, waste and abuse has occurred before; (2) national defense threats when accessing new organizations with entities or operations in countries like China and Russia without the typical restrictions; and (3) the risks of disputes where rules and regulations are not well-defined. In the accompanying 11 Considerations, we identify common concerns, questions and best practices as OTAs continue to expand.

Terms:

Why all the FAR Clauses? – Though OTAs are not subject to the FAR, agreement officers are not precluded from using FAR clauses and since that is what they are trained in, we have seen our fair share of OTAs that do just that. Hopefully education within the government will address this over time, but until then contractors should feel empowered to help their agreement

officer and push back where necessary. The same goes for subcontractors where primes tend to flow down their standard templates. Many of our clients find it easier to negotiate OTA awards as a prime than when in a subcontractor position.

The Consortium Agreement – The terms of the OTA at the consortium level can be restrictive. As a result, some member organizations may experience less flexibility in achieving their optimal outcome using this model, thereby negating some of the OTA appeal. Before signing up, take the time to understand the general terms and conditions of being a consortium member, in addition to the terms and conditions of the OTAs under management, in order to protect your interests (e.g., what data will you provide, how can it be shared, how is it protected, fees, etc.).

Defining Objectives – When the looser structure of an OTA is embraced, sometimes agreement officers have trouble defining the objectives and expected workflow of the effort. Where a stated vision and anticipated steps are beneficial, do not be shy about offering to draft this language for your customer. Without some agreement as to the goals and activities required by the OTA, the chances of a potential dispute will rise.

Proposals/Negotiations:

Fast Awards, Faster Proposals – For the experienced government contractor who is used to longer lead times and slow awards, OTAs are a breath of fresh air, but also a stress on the proposal team. While OTAs are not always faster, they often are and therefore require you to plan ahead, involve leadership early, obtain necessary approvals, and engage third party consultants if needed to support surge efforts.

“Significant Extent” – For DoD OTA proposals involving traditional defense contractors, clearly document the manner in which NDCs participate to a significant extent to maintain eligibility for the award and limit the required cost share. While the current guides provide examples of “significance,” there is no stated threshold to apply and agreement officers are directed to evaluate the totality of the circumstances before making a determination.

Competition and Price Analysis – Current statutes permit agencies to determine what competition will look like, though it should be used to the maximum extent practical. Without it, government buyers are left with the challenge of justifying the price of innovation where market data may not yet be available. Here again, it behooves the contractor to assist the procuring official in making its determination by providing supporting information in the proposal.

Intellectual Property/Data Rights – The ability to maintain proprietary IP is one of the primary draws of OTAs. However, Bayh Dole-like requirements for IP, and FAR/DFARS-esque data rights clauses, are typically the starting point for these agreements.

Know that there is some latitude in negotiating these terms and contractors should endeavor to do so where possible.

Position Yourself with the RFP – Requirements often change throughout the Whitepaper and later phases of the potential OTA award process. Track these changes and respond accordingly to ensure responsiveness. Additionally, if follow-on production work is anticipated as part of the procurement objective and available via sole source methods, position yourself by ensuring such work is explicitly stated in the RFP (to avoid a sustainable protest).

Post-Award:

Cost Accounting – Though OTAs may not be subject to CAS, the traditional defense contractors receiving OTAs could be and must account for costs accordingly. As such, a frequent question is how to account for consortia membership and award fees. Membership fees are typically charged as allowable G&A expenses, whereas award fees may be most appropriately treated as contra-revenue accounts, decrementing revenue received and not affecting expense accounts.

Feedback & Past Performance – Unlike most government contracts where unsuccessful bidders receive a debrief and successful bidders eventually have their performance captured in the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System (CPARS), such records are ostensibly absent in OTAs. Many market participants have complained about the lack of feedback when pursuing OTAs (though at least one consortium reportedly is addressing this). Meanwhile new market participants who develop a taste for federal awards are left without a past performance record on which to draw from in future awards.

Cashflow and Resource Management – Especially for small businesses performing or pursuing OTAs, it is important to understand that these are not the more stable and predictable scopes of work the public sector is known for. Several contractors reported frequent 3-6 month extensions for prolonged research projects that led to cashflow and resource management challenges because it was unclear whether the research projects would last.

OTA use is growing in popularity in DoD and across federal agencies. These eleven considerations offer valuable insight into emerging OTA use cases. Companies that come to the table with a clear understanding and a range of answers will be better able to succeed in this government sandbox.

This article was published in the Spring 2019

Service Contractor magazine.

Click here to view a PDF of this article.